While all my writer friends were at the Ontario Writers Conference this weekend, I was attending the The Globe and Mail Open House Festival at the Toronto Reference Library listening to a panel discussion entitled “The Science of Saving (or Harming) the World.” The panelists were author James Gleick, professor and author, Thomas Homer-Dixon, and theoretical physicist, Lee Smolin . The discussion was moderated by CBC journalist, Helen Mann.

Due to my poor note-taking ability, I’m not going to attribute any direct quotes here. What follows is my take on the overall content and leanings of the discussion. It’s a bit disjointed but I’ve tried to lump together ideas that go together …regardless of when they were delivered and by whom.

Though the topic was climate change, the bulk of the discussion centered on the questions of why science is mistrusted by the public, how people know (or decide) who to trust, and what scientists and journalists can do to foster trust and create a more informed public.

Science and the case for expertise

Science is hard to do well. It takes years of training, discipline, and drudgery to produce ideas worth paying attention to.

Scientists have an ethical commitment to the truth, and as such, science can be viewed as a way to approach to truth. Journalists, seeking to report correct information (such as in the case of climate change) seek out scientists to learn what the current knowledge is. Science can be trusted because the chain of evidence that leads to a particular result can be traced.

Scientists need to have a streak of independence and arrogance in order to challenge current thinking. But they must also have a certain deference to the established knowledge and scientists who have come before them. Finding the sweet spot between those two is the key to becoming successful.

The internet, self-publishing, and other new media have created a low barrier of entry to publication which leads to a diffusion of information beyond the realm of experts. This flattening of the hierarchy has its pros and cons (Wikipedia is an example of both) but in either case, it is inescapable.

Where scientific evidence fundamentally challenges powerful interest groups who have a financial or political stake in maintaining the status quo, such groups are actively working to turn the public against science. They muddy the waters with non-scientific opinions, confusing arguments, and outright lies.

There has been a loss of deference to expert opinion or advice. People are no longer relying on journalists and authority because information is available everywhere. But information should not be confused with knowledge. Knowledge is labour-intensive.

This all creates a climate where the public is unable to discern who to trust; whose “version” of truth is the one to pay attention to.

There is frustration that climate scientists have taken so long to publish a consensus. This only further feeds the public mistrust.

People used to see science as a means to some glorious future, and maybe still do. But there is a growing tendency (perhaps fostered by interest groups) for science to be viewed as unable to solve problems, or even worse, as being the cause of problems.

Part of this skepticism may stem from the fact that science solves the easy problems first –the things that can be addressed quickly to improve the quality of life, such as food production, medicine, and technologies that enhance well-being. But now the problems we face are large and complex (climate change and cancer for instance).

The BP oil spill presents a paradox: There is public mistrust of scientists who are seen to have had a hand in the event (or failed to prevent it) and there is an unreasonable trust in the magical ability of science to solve it.

But science solves background development, not ongoing operations. For example, the BP oil spill; science gave us the means to find oil and to drill through miles of ocean bottom to extract it. The spill was not a failure of science. It was the result of corporate neglect of safe practices, lack of routine maintenance, poor management, and non-compliance with regulations. All of these things are out of the reach of science.

For hunter-gathers only immediate problems needed solving – where to find the next meal, where to sleep. Then came basic agriculture and now humans are committed to planting every year: “We can’t mess this up!” becomes the mantra of survival.

Bigger problems require bigger solutions.

The complexity of today’s world makes it more difficult to prevent, manage, and find solutions for big problems. Material needs and enterprises have expanded to such a degree that the problems that need solving are so hard, the places are so hostile, and the management and maintenance are so complicated, that companies and nations cannot keep up.

Looking ahead

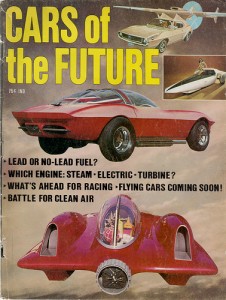

“When we were kids” the future was always present ahead of us; it captured our imagination!

We read science fiction and articles that promised all sorts of fantastic technologies and new ways of living. We worshipped science as a way to get to this amazing future. Now science and technology move so quickly, we’re in the future all the time. It’s no longer present in the public imagination.

Is that really true? Or is that just our view from our older (50+ year old) perspective? In the cold-war era, the science-fiction of the 1960s’ may have been balanced between optimism and pessimism. Does science fiction (or even news) today present a more pessimistic future than in “our day”? Could this be why people have lost faith in science?

With online communities and social media, students today seem to be more insular and narcissistic.

Students are able to retreat into worlds of like-minded communities rather than engage in the larger world. Incoming college students seem to have little awareness of current events and require “remedial” education to bring them up to speed.

But, the opposite case can also be made: For every kid who builds a wall around him or herself 10 others are reaching out and “meeting” people from all walks of life.

Young people are creating global communities in ways that have never been possible before.

Is climate change solvable?

Climate change is solvable, but only if we develop a plan and carry it through. The longer we stay on the current trajectory and do nothing, the less likely we’ll be able to change the outcome.

But there are huge areas of “staggering stupidity” to overcome. We can only solve the big problems if we can sift the knowledge from the flood of noise. We need to develop effective “metrics of merit” to determine whom and what to trust.

Today we have more knowledge than ever before. The question is, how does this knowledge affect how we think about the future? If we know everything about the present, can we change the future or are we on an unalterable path?

Wherever people and ideas connect opportunities for innovation arise. Only through collaboration, transparency, and the open exchange of ideas, will there be potential to explore Steven Johnson’s “adjacent possible” –the extraordinary future we can’t yet imagine.

Recent Comments